Ancestral Voices

1999

3m, 2w; no set. BPP

I understand that in this country, especially in the Midwest, there’s a way of doing plays which is called “Reader’s Theatre.” I don’t know much about it, but I do know that this play, like my Love Letters before it and Screen Play which followed later on, can only work if they are read by actors in front of an audience. These three plays, which jump from place to place and deal with large numbers of characters, would never submit to the restraints and limitations of long rehearsals and traditional staging. Love Letters gets its power by the very fact that its two lovers are confined within letters, and Screen Play pretends to be the scenario for a movie, but I have to admit Ancestral Voices has only its own excuse for simply being read aloud.

I wrote it about my maternal grandparents, probably because at that time I had become a grandparent myself. In the process, I was influenced by specific events and details from my own family, but by the time I finished the play, it contained as many differences as similarities. If I were younger, or had a cousin in Hollywood, I might have originally aimed this story for the screen. Yet when I write, I seem to do better if I have in mind the image of live actors performing in front of responsive audiences. Besides, the theatre, which is an ancient and, in some ways, an outmoded medium, seems to be the best medium for presenting the ancient and outmoded customs which were once so much a part of my life. In any case, for whatever reason, Ancestral Voices works best simply as a sit-down reading. (I once saw a partially staged version which somehow let out all the steam.)

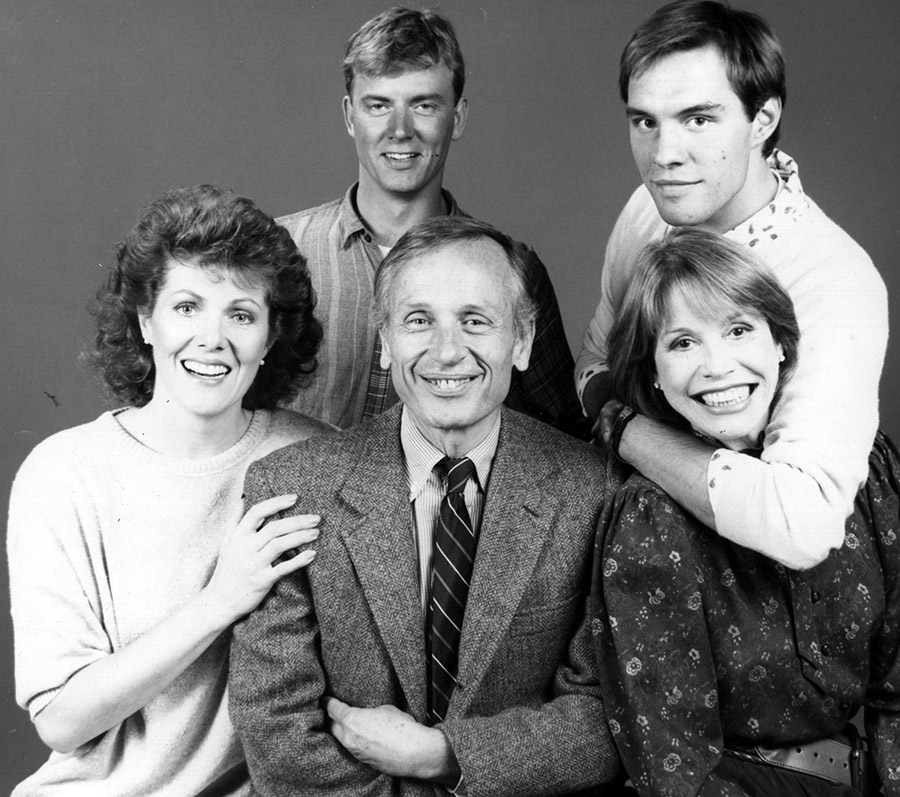

We began to offer the play on successive Sunday and Monday nights at Lincoln Center while another play of mine, Big Bill, was following the conventional Tuesday through Saturday schedule of performances. Our opening night cast for Ancestral Voices consisted of Elizabeth Wilson, Edward Herrmann, David Aaron Baker, Blythe Danner, and Philip Bosco, all of whom seemed easy and comfortable with the form. When the play’s run was extended, the many subsequent teams brought charm and variety to the story. I’ve occasionally performed it myself, playing my own grandfather.

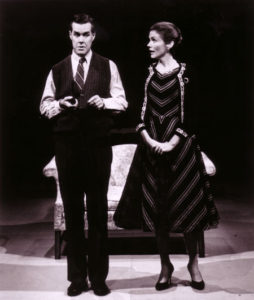

Another Antigone

1987

2m, 2w; fluid set. DPS

Here is one of my many attempts to respond in a contemporary way to a classical work, in this case Sophocles’ great play about rebellion and civil authority. My Creon character is based to some degree on a colleague and friend with whom I taught in the School of Humanities at M.I.T. He was portrayed movingly by George Grizzard in the original production at the Old Globe Theater in San Diego and at Playwrights Horizons in New York. He was staunchly supported by Debra Mooney, who played the Dean of Students. My Antigone, played by Marissa Chibas, herself the daughter of a Cuban revolutionary, is a compilation of several of students from my teaching years. I was also influenced by the essay on “Odysseus’ Scar” in Eric Auerbach’s book MIMESIS, which analyzes the difference between the Greek and the Hebraic ways of looking at the world. If this makes my play sound slightly academic, I suppose it is. Maybe it’s for this reason, despite our fine cast, we didn’t do very well in New York. On the other hand, the play has managed to find some subsequent success on the stages and in the classrooms of various schools and universities.

Black Tie

2011

3m, 2w; single set. DPS

At the age of 80, I feel personally fortunate to have come up with what one might call a hit play, even if it is only playing in a smallish theatre for a relatively short time. I’m not at all sure I have many more plays under my belt, but even if I don’t, I can hardly complain after having written Black Tie. It has been, for me at least, a particularly rewarding experience from beginning to end, providing the collaborative joys and audience responses which engaged me when I first was attracted to this strange and wonderful profession many years ago.

Buffalo Gal

2001 - 2008

3m, 3w; single set. BPP

Every play has its own trajectory, and this one has had a particularly unusual one. It began with a reading at Lincoln Center, went on to a fine production at the Williamstown Theatre Festival with Mariette Hartley playing the lead, then graduated to another good run at Buffalo’s Studio Arena Theatre, with Betty Buckley doing the honors. Yet for about five years after that, nothing much happened to it. Finally, after writing several other plays, I found that Buffalo Gal was still tugging at my sleeve. The original director, John Tillinger, was unavailable to work on it any more, so I offered the play to Mark Lamos, with whom I had worked several times before. Together we cut it, eliminated the intermission, tinkered with the ending, and brought the play up to date. The producers at Primary Stages, who by that time had done several other plays of mine, were willing to give this lady with a checkered past another chance.

Meanwhile American culture had changed as well, and the themes of obsolescence and loss in the play seemed now to have more relevance. So we opened almost eight years after the play’s first reading, with an excellent star, Susan Sullivan, and an unusually good supporting cast composed of James Waterston, Mark Blum, Jennifer Regan, Carmen M. Herlihy, and Dathan Williams, We garnered a generally enthusiastic response from the New York critics. Our audiences, too, were enthusiastic, buying into the play from its first preview and enabling us to extend our limited run. So it looks like this pre-owned vehicle, refurbished, tuned up, and differently detailed, may have finally turned out to be one of my more successful endeavors.

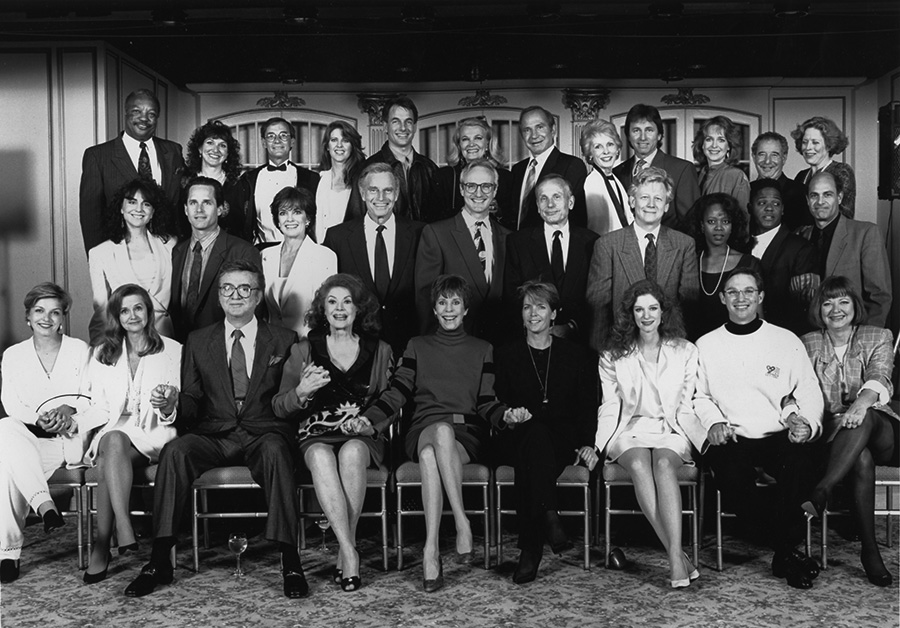

A Cheever Evening

1994

3m, 3w; fluid set. DPS

I’ve always admired the work of John Cheever. The first serious play I ever wrote was an adaptation of his short story “The Day the Pig Fell in the Well”, and when I sent it to him, he gave me considerable encouragement. When I needed him to give me the rights to use elements of his “Goodbye, My Brother” in my play Children, he threw in the rights to the “Pig” story as well. A few years after Children was produced, I was asked to adapt his story “O Youth and Beauty!” for PBS television. In 1993, I found myself reading “Cheever’s Collected” Stories once again, and was struck again by the sharp specificity of his dialogue and the humor and mystery pervading so many of his pieces. I sketched out an evening of scenes and monologues from his work, where the first half would focus on stories set in Manhattan and the Westchester suburbs during the winter months, while the second half would deal with vacations, summer houses, and various centrifugal effects on the family. Don Scardino, at that time the Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons, staged a fund-raising reading of this collage-like collection of scenes, and I invited Mrs. Cheever to take a look. She ultimately gave us the rights to present A Cheever Evening as a fully-staged play, so stage it we did, with a first rate cast. John Cunningham, Jack Gilpin, and Robert Stanton played Cheever’s restless men, while Mary Beth Peil, Julie Hagerty, and Jennifer Van Dyck played his anxious women.

I’ve always admired the work of John Cheever. The first serious play I ever wrote was an adaptation of his short story “The Day the Pig Fell in the Well”, and when I sent it to him, he gave me considerable encouragement. When I needed him to give me the rights to use elements of his “Goodbye, My Brother” in my play Children, he threw in the rights to the “Pig” story as well. A few years after Children was produced, I was asked to adapt his story “O Youth and Beauty!” for PBS television. In 1993, I found myself reading “Cheever’s Collected” Stories once again, and was struck again by the sharp specificity of his dialogue and the humor and mystery pervading so many of his pieces. I sketched out an evening of scenes and monologues from his work, where the first half would focus on stories set in Manhattan and the Westchester suburbs during the winter months, while the second half would deal with vacations, summer houses, and various centrifugal effects on the family. Don Scardino, at that time the Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons, staged a fund-raising reading of this collage-like collection of scenes, and I invited Mrs. Cheever to take a look. She ultimately gave us the rights to present A Cheever Evening as a fully-staged play, so stage it we did, with a first rate cast. John Cunningham, Jack Gilpin, and Robert Stanton played Cheever’s restless men, while Mary Beth Peil, Julie Hagerty, and Jennifer Van Dyck played his anxious women.

Children

1974

1m, 3w; single set. DPS

The English critics are not always hospitable to American work, and it seems especially not to mine, but most of them liked this one. Its success in England gave the play enough momentum to interest producers in the U.S. and helped get me promoted at M.I.T. David Merrick optioned it for a while, and another New York producer dallied with it, before telling me that he’d put it on only if I paid for earphones and simultaneous translations for New York’s Jewish audiences. Ultimately Lynne Meadow at the Manhattan Theatre Club decided to run with the ball. Her production was directed by Melvin Bernhardt, and starred Nancy Marchand , Swoosie Kurtz, Holland Taylor, and Dennis Howard.

The English critics are not always hospitable to American work, and it seems especially not to mine, but most of them liked this one. Its success in England gave the play enough momentum to interest producers in the U.S. and helped get me promoted at M.I.T. David Merrick optioned it for a while, and another New York producer dallied with it, before telling me that he’d put it on only if I paid for earphones and simultaneous translations for New York’s Jewish audiences. Ultimately Lynne Meadow at the Manhattan Theatre Club decided to run with the ball. Her production was directed by Melvin Bernhardt, and starred Nancy Marchand , Swoosie Kurtz, Holland Taylor, and Dennis Howard. The Cocktail Hour

1988

1m, 3w; single set. DPS

Crazy Mary

2007

2m, 3w; single set. BPP

The Dining Room

1982

3m, 3w; simple set. DPS

Family Furniture

2013

2m, 3w; fluid set. DPS

The Fourth Wall

1992/2002

2m, 2w; single set. DPS

The Golden Age

1983

1m, 2w; single set. DPS

The Grand Manner

2010

2m, 2w; single set. DPS

This proved to be one of the best experiences I have had in the theatre. Produced in the Mitzi Newhouse theatre at Lincoln Center in the summer of 2010, it was an attempt to expand retrospectively upon a brief meeting I had had with the actress Katharine Cornell when she was playing in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra in 1948. The director, Mark Lamos, and I had worked together several times before and were very much in synch from when I first showed him the play. I was also comfortable with the producer, Andre Bishop, who had done a number of my plays over the years. The cast of four – Kate Burton, Boyd Gaines, Brenda Wehle, and Bobby Steggert – all connected with each other beautifully and gave their characters a richness of dimension beyond what I thought I had written. The glamorous costume designs were rigorously researched by Annie-Huild Ward, and the set – the Green Room of a Broadway theatre – was created out of nothing by John Arnone since no Broadway theatres had Green Rooms at that time. During rehearsal, we tinkered very little with the script, confining ourselves to long discussions but few cuts, and once we were in previews, audience responses were enthusiastic enough to enable us to run with the ball pretty much without interference. Most of the critics were enthusiastic, though the New York Times, as is usual with my plays, gave us a disappointing shrug. In any case, audiences kept coming and responding, the actors kept growing in their parts, and The Grand Manner became an excellent example of why the theatre can be such an exciting profession when everyone works together so collaboratively.

The Guest Lecturer

1998

2m, 2w; single set. BPP

This is an attempt to explore, dramatically and comically, the primitive roots of drama. It asks the audience, in effect, to collaborate on a ritual murder in the hope of purging the community of its inherent guilt. (I had tried to some degree the same sort of thing several years before in a shorter play called The Open Meeting, and of course Shirley Jackson deals with the same theme more seriously in her story The Lottery.) We opened the play at the George Street Playhouse in New Jersey, directed by John Rando, with Robert Stanton, Nancy Opel, and Rex Robbins, all first rate actors and especially adept at comedy. I can’t say we bowled the audience over, though I noticed that whenever there were younger people in the house, the play seemed to pay off the way we had hoped it would. In New Jersey, I coupled it with a short one-act called Darlene, and five years later in New York, paired it with my more seasoned curtain-raiser, The Problem. Once again Primary Stages, as it had with The Fourth Wall and would again with Buffalo Gal,was willing to give a play of mine a second chance. This time, we opened it under the overall title of Strictly Academic, directed by Paul Benedict, with Susan Greenhill, Keith Reddin, and Remy Auberjenois. They were good actors and got most of our laughs all right, but maybe I’ve had enough of fertility rituals for a while.

This is an attempt to explore, dramatically and comically, the primitive roots of drama. It asks the audience, in effect, to collaborate on a ritual murder in the hope of purging the community of its inherent guilt. (I had tried to some degree the same sort of thing several years before in a shorter play called The Open Meeting, and of course Shirley Jackson deals with the same theme more seriously in her story The Lottery.) We opened the play at the George Street Playhouse in New Jersey, directed by John Rando, with Robert Stanton, Nancy Opel, and Rex Robbins, all first rate actors and especially adept at comedy. I can’t say we bowled the audience over, though I noticed that whenever there were younger people in the house, the play seemed to pay off the way we had hoped it would. In New Jersey, I coupled it with a short one-act called Darlene, and five years later in New York, paired it with my more seasoned curtain-raiser, The Problem. Once again Primary Stages, as it had with The Fourth Wall and would again with Buffalo Gal,was willing to give a play of mine a second chance. This time, we opened it under the overall title of Strictly Academic, directed by Paul Benedict, with Susan Greenhill, Keith Reddin, and Remy Auberjenois. They were good actors and got most of our laughs all right, but maybe I’ve had enough of fertility rituals for a while.

Heresy

2012

4m, 3w; single set. DPS

Human Events

2001

3m, 2w; fluid set. BPP

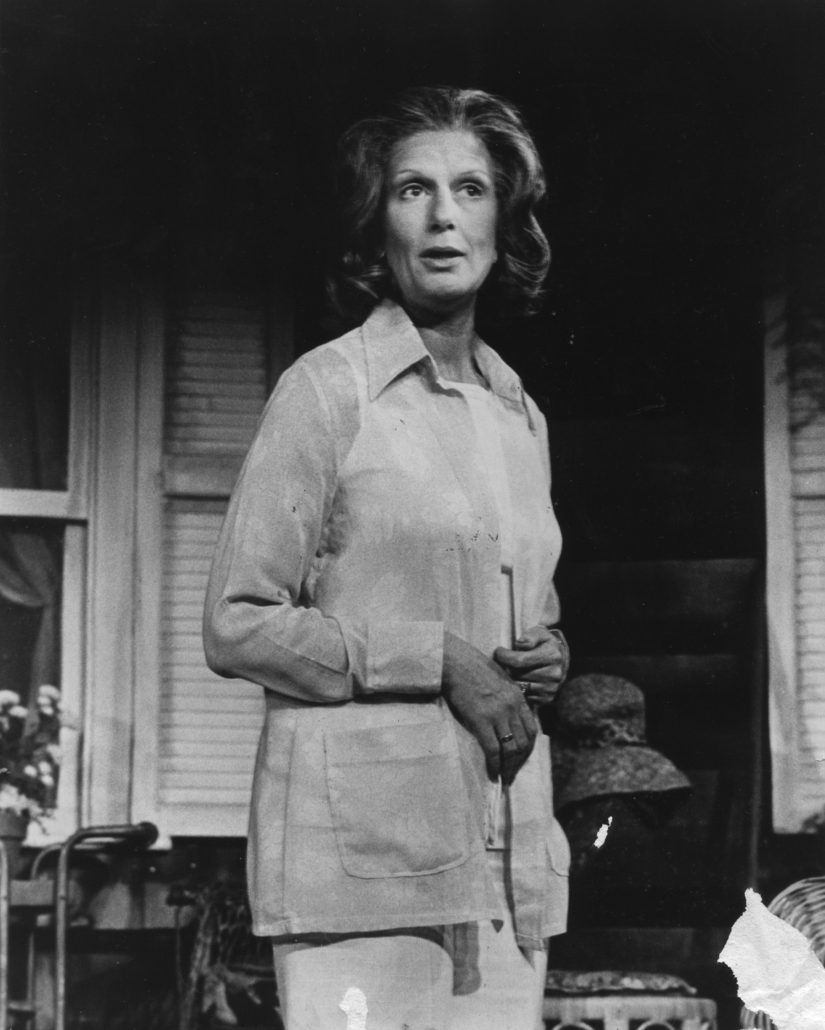

Labor Day

1998

3m, 2w; single set. DPS

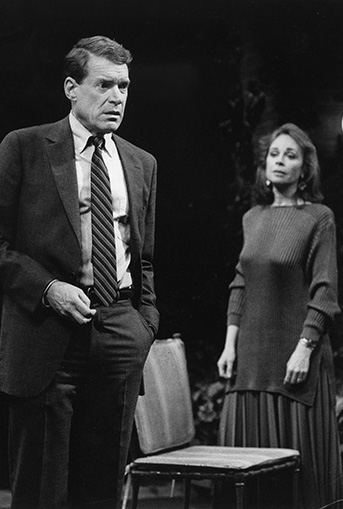

Later Life

1993

2m, 2w; single set. DPS

Henry James, once again, peeks out behind this one, as he did behind my play The Golden Age. His great story “The Beast in the Jungle” certainly influenced the play’s theme, which is about the ache and sadness of a life not lived. The plot, in my case, has to do with a divorced man who happens to reconnect with an old flame at a party on a terrace overlooking Boston harbor. Romantically directed by Don Scardino, the play focuses on a middle aged man who is unable to risk making a definitive move towards the woman who in the past and again tonight might offer him a more vital future, As the exuberant life of the party swirls around him, with many guests coming and going, interrupting, bickering, explaining, but always committed to living their lives, even as our hesitant hero seems unwilling or unable to change his own.

Henry James, once again, peeks out behind this one, as he did behind my play The Golden Age. His great story “The Beast in the Jungle” certainly influenced the play’s theme, which is about the ache and sadness of a life not lived. The plot, in my case, has to do with a divorced man who happens to reconnect with an old flame at a party on a terrace overlooking Boston harbor. Romantically directed by Don Scardino, the play focuses on a middle aged man who is unable to risk making a definitive move towards the woman who in the past and again tonight might offer him a more vital future, As the exuberant life of the party swirls around him, with many guests coming and going, interrupting, bickering, explaining, but always committed to living their lives, even as our hesitant hero seems unwilling or unable to change his own. A Light Lunch

2008

2m, 2w; simple set. BPP

Love Letters

1988

1m, 1w; no set. DPS

Love and Money

2015

2m, 3w; single set. DPS

The Middle Ages

1978

2m, 2w; single set. DPS

Mrs. Farnsworth

2004

3m, 3w; single set. BPP

O Jerusalem

2003

2m, 3w; simple set. BPP

As one of it characters announces at the beginning of this play, it was written soon after 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. It was first performed at the Flea Theatre in lower Manhattan, a small, youthful organization which had recently gained a reputation for putting on plays with political implications. It would subsequently produce several other plays of mine during these anxious years. Jim Simpson, the artistic director, directed O Jerusalem himself at a time when I doubt if many other theatres in New York would have touched the play. He rounded up a first-rate cast headed by Stephen Rowe, who played a liberal Texan, and crony of President George W. Bush, whose State Department appointment takes him to the Middle East and into the turmoil swirling around 9/11. Rita Wolfe played a Palestinian woman whom he knew in simpler days, and Priscilla Shanks played his current female companion.

As one of it characters announces at the beginning of this play, it was written soon after 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. It was first performed at the Flea Theatre in lower Manhattan, a small, youthful organization which had recently gained a reputation for putting on plays with political implications. It would subsequently produce several other plays of mine during these anxious years. Jim Simpson, the artistic director, directed O Jerusalem himself at a time when I doubt if many other theatres in New York would have touched the play. He rounded up a first-rate cast headed by Stephen Rowe, who played a liberal Texan, and crony of President George W. Bush, whose State Department appointment takes him to the Middle East and into the turmoil swirling around 9/11. Rita Wolfe played a Palestinian woman whom he knew in simpler days, and Priscilla Shanks played his current female companion. If this device helped build a communal effect, I have to admit that the play also stepped on a few toes.. The nation of Israel doesn’t get off the hook in this one, with the result that O Jerusalem became the only play I’ve written to have been reviewed twice by the New York Times, both times as “flawed” and “misguided.” Nonetheless, O Jerusalem was revived fairly recently in 2008 in a one-night reading sponsored by the Public Theatre. With Bill Irwin playing the lead , supported by the rest of the original cast, it seemed to hold up fairly well both in the performance and during the discussion afterwards which was chaired by former U.N. Ambassador Richard Holbrooke.

Office Hours

2010

3m, 3w; multiple set. DPS

The Old Boy

1991

4m, 2w; fluid set. DPS

The Perfect Party

1986

2m, 3w; single set. DPS

Post Mortem

2006

1m, 2w; simple set. BPP

Screen Play

2005

4m, 2w; no set. BPP

Here is another play, like Love Letters, designed to be read by actors, this time standing at music stands. This is also another play set in my hometown, Buffalo, New York. And I have to say it is another play with a strong underlying political theme. It is intended to be a kind of homage to, and reworking of, the movie Casablanca, and I suspect it works best when the audience is at least somewhat familiar with this great classic. We did this play off-off-Broadway in a small space at the Flea Theatre, casting it with young, non-Equity actors who were just entering the profession. Their youthfulness and energy, coupled with the simple but ingenious staging by Jim Simpson, made Screen Play into something of a success here in New York and I hoped it would be picked up by many schools and colleges. But so far, it hasn’t been done much. Maybe Casablanca is no longer the icon it has always been to me and my generation, or maybe my play’s political paranoia, which sees a parallel between German occupations of various countries in the early Forties to the Bush administration’s recent intrusions into American life, is a conceit that doesn’t hold up in the long run. We’ll see…

Here is another play, like Love Letters, designed to be read by actors, this time standing at music stands. This is also another play set in my hometown, Buffalo, New York. And I have to say it is another play with a strong underlying political theme. It is intended to be a kind of homage to, and reworking of, the movie Casablanca, and I suspect it works best when the audience is at least somewhat familiar with this great classic. We did this play off-off-Broadway in a small space at the Flea Theatre, casting it with young, non-Equity actors who were just entering the profession. Their youthfulness and energy, coupled with the simple but ingenious staging by Jim Simpson, made Screen Play into something of a success here in New York and I hoped it would be picked up by many schools and colleges. But so far, it hasn’t been done much. Maybe Casablanca is no longer the icon it has always been to me and my generation, or maybe my play’s political paranoia, which sees a parallel between German occupations of various countries in the early Forties to the Bush administration’s recent intrusions into American life, is a conceit that doesn’t hold up in the long run. We’ll see…

Sweet Sue

1986

2m, 2w; single set. DPS

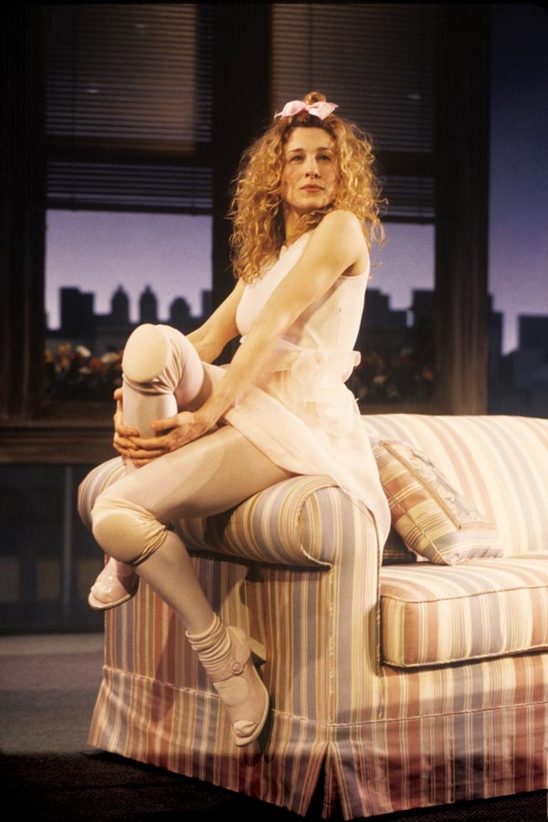

Sylvia

1995

2m, 2w; fluid set. DPS

They say that great ideas can be contagious at certain times. A few years after my play was produced, Edward Albee took a more drastic look at the same subject in a play where a man falls passionately in love with a goat. The protagonist becomes so serious about his relationship that his wife determines to kill the animal. My Sylvia dies, too, but being a sentimental soul, I have her death bring about a return to marital harmony. I don’t know whether Albee’s s goat’s name is Sylvia or not, but he subtitles his play “Who is Sylvia?” which I like to think is an homage to mine. Or else he is simply quoting Shakespeare’s poem, “Who is Sylvia?” as I do in my play. In any case, both plays have done well. Mine has played all over the world, from France to China – except for England, where a snappy production directed by Michael Blakemore and starring Zoe Wanamaker was roundly dismissed by the British critics with the same impatience that they’ve shown toward my other work. I suspect Albee’s play did well there, proving that the English fall in love more easily with goats than with dogs.

Drawing by Jim Stevenson

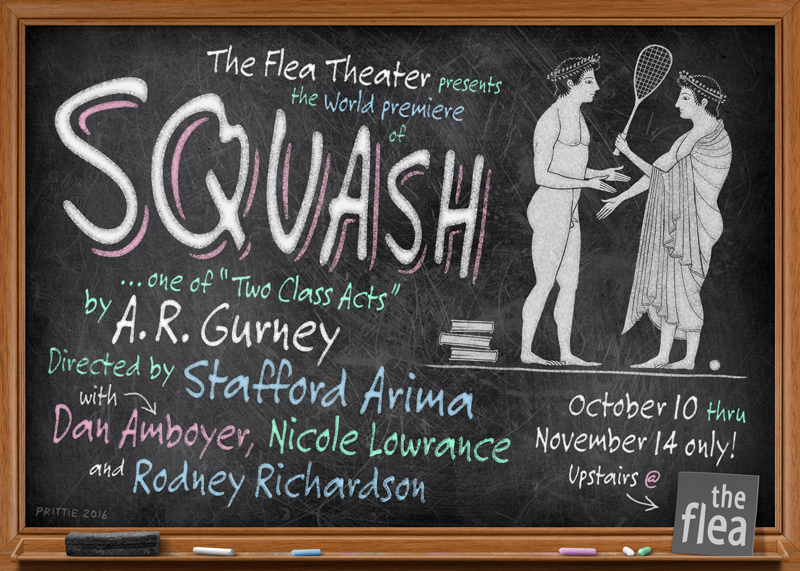

Two Class Acts

2016

Ajax:

1m, 1w; classroom set. DPS

Squash:

2m, 1w; 4 partial sets. DPS

Two Class Acts is composed of two separate plays, each about an hour long. They can be performed over the same evening, or separately at different times by different organizations in different places. Both plays call for small casts and simple sets, and both deal in various ways with classical Greek culture as it continues to affect us. These two plays of mine were the last to be performed by the original Flea Theater on Church Street in the Tribeca area of New York City. Over the years, this gutsy organization has presented much new work, my own included. It has now bought a building in the same general area, but several blocks south . Within this building, the Flea has carefully designed and built several different types of spaces for various kinds of plays, along with ample administrative and rehearsal spaces to attend them. Since the Flea has consistently been the home of talented people involved in all aspects of the theatre, we can look forward to many exciting works emerging from their new spaces.

What I Did Last Summer

1982

2m, 4w; fluid set. DPS

After a successful run on the summer circuit with Eileen Heckart playing the lead, the play opened in New York at the Circle Repertory Theatre, a generous–spirited, cooperative organization on Sheridan Square, run by the playwright Lanford Wilson, the director Marshall W. Mason, and the actress Tanya Berezin . Despite their good will, we had a complicated gestation period. One of the lead actors had to be let go late in rehearsal, and soon afterwards the original director was replaced as well. The substitute director refused to lend his name to the project. The night we opened, the toilet in the men’s room overflowed and a man had a heart-attack in the second row. The reviews weren’t much good, but I comfort myself into thinking the critics may have been perplexed by our lack of a director and distracted by what was happening in the audience. In any case, What I Did Last Summer has survived to find a healthy life in high schools, especially in Texas and the Southwest.

What I Did Last Summer

2015

2m, 4w; fluid set. DPS

Afterthought: This play was revived in mid-2015 as the second of three plays I had been invited to offer under the auspices of the Signature Theater and its artistic director James Houghton. Imaginatively directed by Jim Simpson from the Flea Theater, who threw away most of the scenery the script had originally called for and gave it a simple background with occasional rear-screen projections, along with a professional drummer to introduce or punctuate its various scenes. The result was a group of wonderfully original performances by a first-rate cast. What I Did Last Summer had been reasonably successful in schools and colleges throughout the country over the past thirty years. But this new and fresh New York production felt especially rewarding and made me all the more appreciative of the variety and energy invoked by different productions of American plays.