Big Bill

2003

8m, 1w; single fluid set. BPP

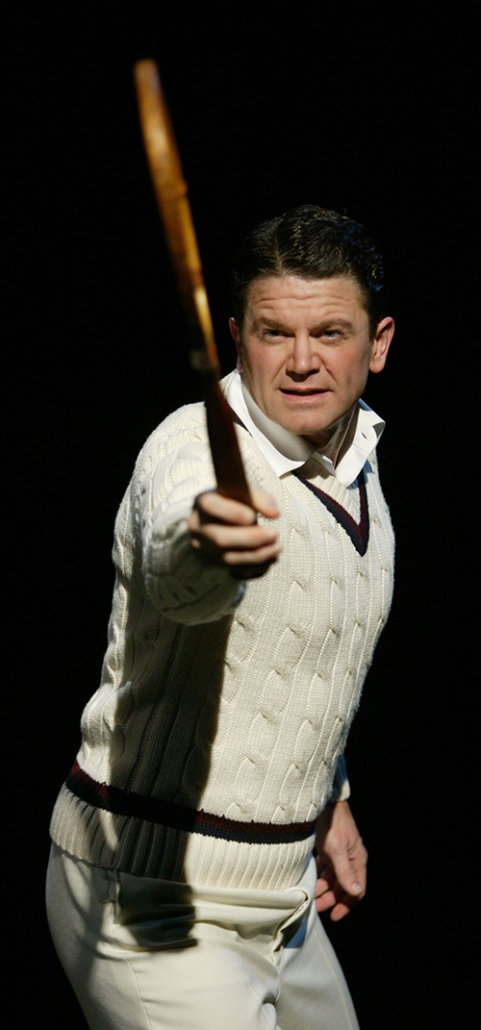

I saw elements of tragedy in Tilden’s rise and fall, and by staging his story in a kind of abstract tennis stadium, with four ball boys serving as fans and friends, as well as stage hands and a pseudo-chorus, I hoped to give it a kind of theatrical ingenuity, and so avoid the kind of traps that come with what Hollywood calls a “bio-pic.” I also saw a challenge in writing a play about tennis, a favorite sport of mine, without ever having to show an actual game on stage. Mark Lamos directed, and John Lee Beatty designed, the initial production at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and then at Lincoln Center, where it was beautifully produced by Andre Bishop and Bernard Gersten. John Michael Higgins played Tilden with style and élan, David Cromwell and Stephen Rowe played the mature male roles, the various Ballboys played various youths, and and Margaret Welch played all the women.

I saw elements of tragedy in Tilden’s rise and fall, and by staging his story in a kind of abstract tennis stadium, with four ball boys serving as fans and friends, as well as stage hands and a pseudo-chorus, I hoped to give it a kind of theatrical ingenuity, and so avoid the kind of traps that come with what Hollywood calls a “bio-pic.” I also saw a challenge in writing a play about tennis, a favorite sport of mine, without ever having to show an actual game on stage. Mark Lamos directed, and John Lee Beatty designed, the initial production at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and then at Lincoln Center, where it was beautifully produced by Andre Bishop and Bernard Gersten. John Michael Higgins played Tilden with style and élan, David Cromwell and Stephen Rowe played the mature male roles, the various Ballboys played various youths, and and Margaret Welch played all the women.

I saw elements of tragedy in Tilden’s rise and fall, and by staging his story in a kind of abstract tennis stadium, with four ball boys serving as fans and friends, as well as stage hands and a pseudo-chorus, I hoped to give it a kind of theatrical ingenuity, and so avoid the kind of traps that come with what Hollywood calls a “bio-pic.” I also saw a challenge in writing a play about tennis, a favorite sport of mine, without ever having to show an actual game on stage. Mark Lamos directed, and John Lee Beatty designed, the initial production at the Williamstown Theatre Festival and then at Lincoln Center, where it was beautifully produced by Andre Bishop and Bernard Gersten. John Michael Higgins played Tilden with style and élan, David Cromwell and Stephen Rowe played the mature male roles, the various Ballboys played various youths, and and Margaret Welch played all the women.

Far East

1999

3 m, 1 w, 1 w “reader”, 2 on-stage assistants (either sex), 1 percussionist-musician; BPS

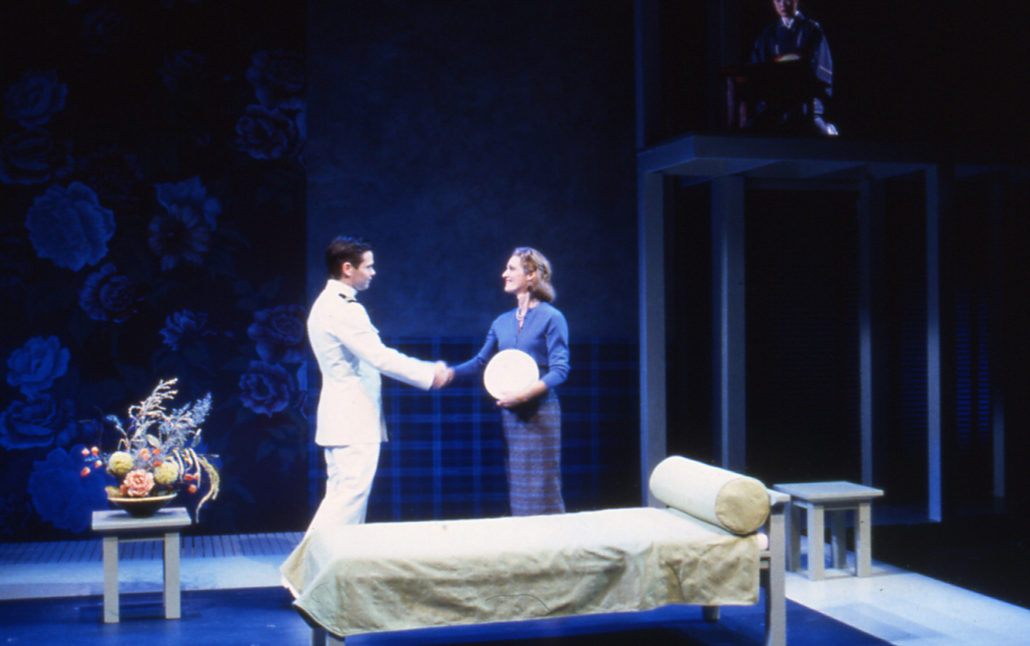

This play has four major roles, but also incorporates a supporting cast as it makes use of several devices from the Japanese Noh and Kabuki theatres. Here we have the “Reader”, probably to be played by an Asian-American woman, who narrates certain events and sometimes enters into them. The play also calls for two black-garbed ,and therefore “invisible”, stage hands, who change scenery and bring on props in full view of the audience. Far East also needs a musician who provides live musical accompaniment and exotic sound effects along the way.

This play has four major roles, but also incorporates a supporting cast as it makes use of several devices from the Japanese Noh and Kabuki theatres. Here we have the “Reader”, probably to be played by an Asian-American woman, who narrates certain events and sometimes enters into them. The play also calls for two black-garbed ,and therefore “invisible”, stage hands, who change scenery and bring on props in full view of the audience. Far East also needs a musician who provides live musical accompaniment and exotic sound effects along the way.

This play has four major roles, but also incorporates a supporting cast as it makes use of several devices from the Japanese Noh and Kabuki theatres. Here we have the “Reader”, probably to be played by an Asian-American woman, who narrates certain events and sometimes enters into them. The play also calls for two black-garbed ,and therefore “invisible”, stage hands, who change scenery and bring on props in full view of the audience. Far East also needs a musician who provides live musical accompaniment and exotic sound effects along the way.

The initial production of the play took place at the Williamstown Theatre Festival. with Scott Wolfe, Bill Smitrovitch, and Linda Emond playing the leads. It was directed by my friend Dan Sullivan. The play then moved promptly to Lincoln Center with Sullivan still directing,. It landed in the same theatre, now called the Mitzi E. Newhouse, where he had directed my Scenes from American Life over twenty-five years before. The New York cast of Far East consisted of Michael Hayden, Bill Smitrovitch , Connor Trinnear and Lisa Emery. The scenery was designed by Tom Lynch who provided several gorgeous Japanese backdrops.

The initial production of the play took place at the Williamstown Theatre Festival. with Scott Wolfe, Bill Smitrovitch, and Linda Emond playing the leads. It was directed by my friend Dan Sullivan. The play then moved promptly to Lincoln Center with Sullivan still directing,. It landed in the same theatre, now called the Mitzi E. Newhouse, where he had directed my Scenes from American Life over twenty-five years before. The New York cast of Far East consisted of Michael Hayden, Bill Smitrovitch , Connor Trinnear and Lisa Emery. The scenery was designed by Tom Lynch who provided several gorgeous Japanese backdrops.

Far East was ultimately produced more realistically by Jac Venza for “Great Performances” on Public Television,, again carefully directed by Dan Sullivan. The play has also had good runs at several regional theatres.

Indian Blood

2006

5m, 3w; single fluid set. BPP

This play took shape over ten years ago as a section of a novel I was trying to write about my four grandparents, not long after I had become a grandparent myself. The first half of the book ultimately became the play Ancestral Voices, which is presented as a kind of chamber play, while Indian Blood morphed into a short story to be promptly rejected by The New Yorker.

This play took shape over ten years ago as a section of a novel I was trying to write about my four grandparents, not long after I had become a grandparent myself. The first half of the book ultimately became the play Ancestral Voices, which is presented as a kind of chamber play, while Indian Blood morphed into a short story to be promptly rejected by The New Yorker. The plot of the play might be summarized as the story of an adolescent boy trying to stretch his wings in a large and traditional family. We rehearsed and opened in the summer, a time which enabled us to garner an unusually able ensemble of actors, all of whom deserve to be listed immediately: Charles Socarides played Eddie, Jeremy Blackman his jealous cousin, John Mc Martin and Pamela Payton-Wright his grandparents, Jack Gilpin his father, and Rebecca Luker his mother. Katherine McGrath and Matthew Arkin played everyone else. Rebecca Luker, a top-flight soprano, managed the Herculean task of modifying her voice into that of a competent amateur when she sang Cole Porter’s “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home to” at the family piano, and the sense of a talent suppressed made the moment all the more effective.

Indian Blood went over well with audiences and most reviewers, though it evoked a cynical shrug from the New York Times which found it all a little too Normal Rockwell. The play won the Outer Critics award at the end of the season, and seems to be continuing its life in high schools and community theatre productions. The process of finding the right form for this material, and then working on it with Mark Lamos, the actors, and designers, and feeling it connect with audiences at 59 East 59th St, a small, wonderfully cozy theatre space, gave me one of the most fruitful experiences in my career.

Indian Blood went over well with audiences and most reviewers, though it evoked a cynical shrug from the New York Times which found it all a little too Normal Rockwell. The play won the Outer Critics award at the end of the season, and seems to be continuing its life in high schools and community theatre productions. The process of finding the right form for this material, and then working on it with Mark Lamos, the actors, and designers, and feeling it connect with audiences at 59 East 59th St, a small, wonderfully cozy theatre space, gave me one of the most fruitful experiences in my career. Overtime

1995

6m, 3w, single set. DPS

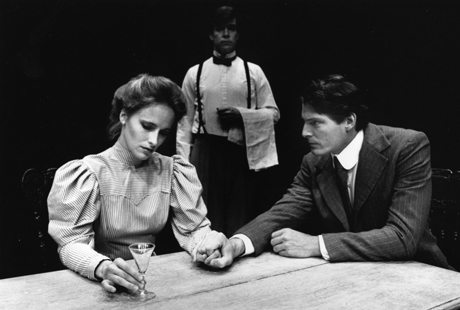

Richard Cory

1976

5m, 3w (minimum); fluid set. SF

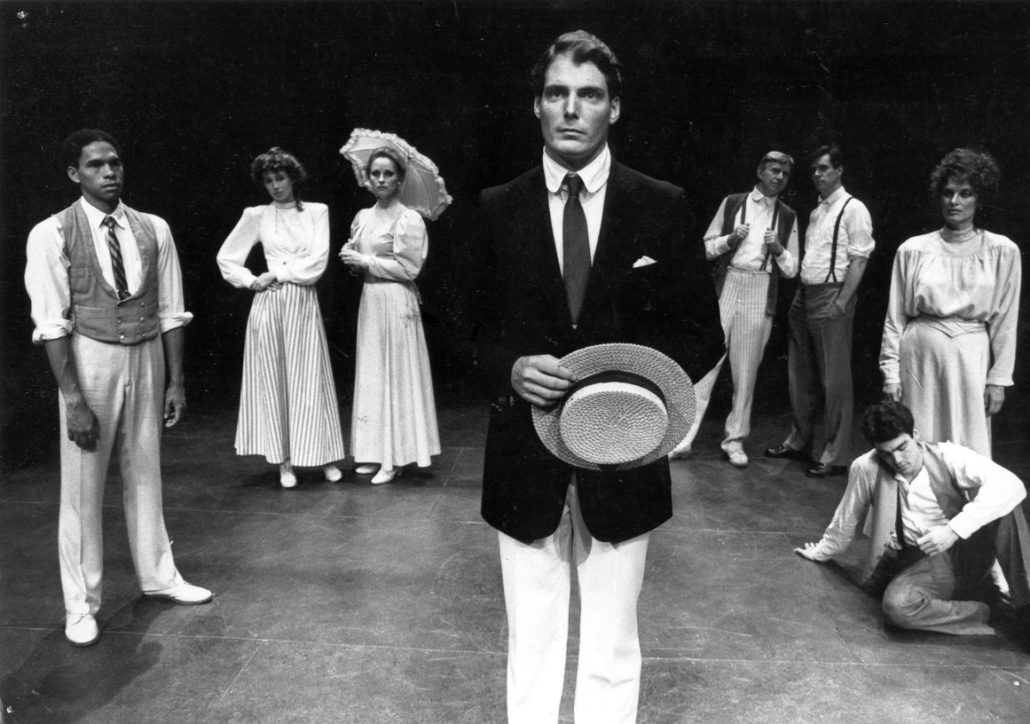

I changed the title to simply Richard Cory when I revised it the Williamstown Theatre Festival ten years later as a vehicle for the actor Christopher Reeve. In this case, without an intermission and with a charismatic star, the play did much better, though on opening night we lost power and had to quit halfway through. The critic from the Boston Globe announced he’d review it anyway and proceeded to pan it.

I changed the title to simply Richard Cory when I revised it the Williamstown Theatre Festival ten years later as a vehicle for the actor Christopher Reeve. In this case, without an intermission and with a charismatic star, the play did much better, though on opening night we lost power and had to quit halfway through. The critic from the Boston Globe announced he’d review it anyway and proceeded to pan it.

I changed the title to simply Richard Cory when I revised it the Williamstown Theatre Festival ten years later as a vehicle for the actor Christopher Reeve. In this case, without an intermission and with a charismatic star, the play did much better, though on opening night we lost power and had to quit halfway through. The critic from the Boston Globe announced he’d review it anyway and proceeded to pan it.

Scenes from American Life

1971

4m, 4w (minimum); single set. SF

The Snow Ball

1991

8m, 8w (minimum); fluid set. DPS

The Wayside Motor Inn

1977

4m, 4w; single set. DPS

The Wayside Motor Inn

2015

4m, 4w; single set. DPS